Early Romantic

Schubert, Mendelssohn, Schumann

Schubert 1797-1828 (31years)

Mendelssohn 1809-1847 (38 years)

Schumann 1810-1856 (46 years)

What amazingly short lives these marvellous composers all lived! I’ve lived almost twice as long as Schumann, and three times as long as Schubert.

The turn of a new century is often marked by quite strong cultural shifts:

1600 saw the end of the old polyphonic style and the emergence of a more self-aware, dramatic manner, typified by Monteverdi’s Orfeo and the Seconda Prattica.

1700 witnessed the birth of the Enlightenment; a major cultural change which opened the door to the Galant and Classical styles.

1800 saw an even more profound shift. Mozart’s world always had a basis of courtly entertainment. Haydn wrote in a similar way, but for a steadily more Bourgeois audience But now compare Schumann. Nothing abstract here; the listener is invited, perhaps commanded, to summon up pictures, to be aware of his or her feelings. We have moved from an era of Manners to one of Personal Expression. And from indoors to outdoors, to Nature and fresh air.

There were two major reasons for this cultural change, both described by the same word: Revolution. First of all: War. By the time of Waterloo in 1815, Europe had been torn by war for nearly twenty years. The relief of of the new urban middle classes, in what is often called the Biedermeier period, can clearly be felt in Mendelssohn’s and Schumann’s music.

The second reason was of course Beethoven, who epitomised the stress of the Napoleonic wars, but also provided models for a new kind of Sensibility.

Nevertheless, after his overwhelming revolutionary power, our Early Romantic composers forged a very different path. They could be influenced by Beethoven’s descriptive Pastoral but, along with perhaps a majority of their contemporary music lovers, they found the wildness of the Eroica and the Choral much less to their liking. However the Pastoral showed them how a symphony could be descriptive rather than argumentative, and they leapt at that suggestion. They painted pictures; they told stories.

Interestingly not one of them wanted to be like Beethoven.

Three examples:

1. Much of Schubert’s big C major symphony was written during a walking tour of the Salzburg/Gastein region. It’s spondaic march rhythm dominates all four movements, giving it almost the feeling of a diary. It’s his Sommerreise.

2. Mendelssohn, who was also a very talented water-colourist, wrote what you might call symphonic post cards of Scotland and Italy for his less well-off, less well-travelled friends. Notice that his first symphony was written during Beethoven’s lifetime. Not a trace of the Master’s influence there: it sounds like Mozart.

3. Schumann wrote beautiful, poetic symphonies about the Spring, and the Rhine, equally untouched by Beethoven. As we saw in the last class, only Berlioz carried the dramatic Beethoven torch forward.

Do you remember the Six Sss that I use to examine any piece from a historical point of view?

Sources, Size, Seating, Sound, Speed, Style

This matrix doesn’t tell you how to play a piece. But it does give a historical context to what is after all historical music. It helps us to play a piece in a way the composer might have expected, and to avoid making embarrassing stylistic mistakes.

Each composition is still there for you to recreate, in this case in a gentle Early Romantic style.

Let’s look at The Six S’s for all three composers. The feel of the style is much more what we are used to today. We do not have to deal with so many of the demanding rules of the Classical period. But in spite the new, more Romantic, sound world, we shouldn’t exaggerate, but keep things relatively simple. Our composers inherited and valued the Classical style of the previous century. And indeed Schubert of course still inhabited Vienna, and was raised in her traditions.

S for SOURCES

1. Ludwig Spohr. All three of our composers inherited his style, (Violinschule 1832). Famous for his “serious” approach to the Classical repertoire, and for grand on-string bowing. He was a big influence on the whole 19th century.

2. Ferdinand David (1810-1873) studied violin with Spohr for 2 years. He was also enormously influential, with dozens of editions of chamber music classics, and with his Violinschule of 1863. He was Mendelssohn’s chosen Konzertmeister in Leipzig from 1835, and premiered the Violin Concerto. He was appointed the first professor of Violin at the new Leipzig Conservatoire, and would have been personally known to Schumann.

In his editions he suggests with a wiggly line where one could vibrate. That marking appears only a few times per page of music. The so-called “undulation” is clearly just an expressive decoration.

He used horizontal lines under a slur for portato.

Strokes for staccato, on or off the string (Sautillé).

He shows Martellé at the bow point (like Spohr),

but now also possible in the middle of the bow.

For him grace notes are now definitely before the beat.

S for SIZE

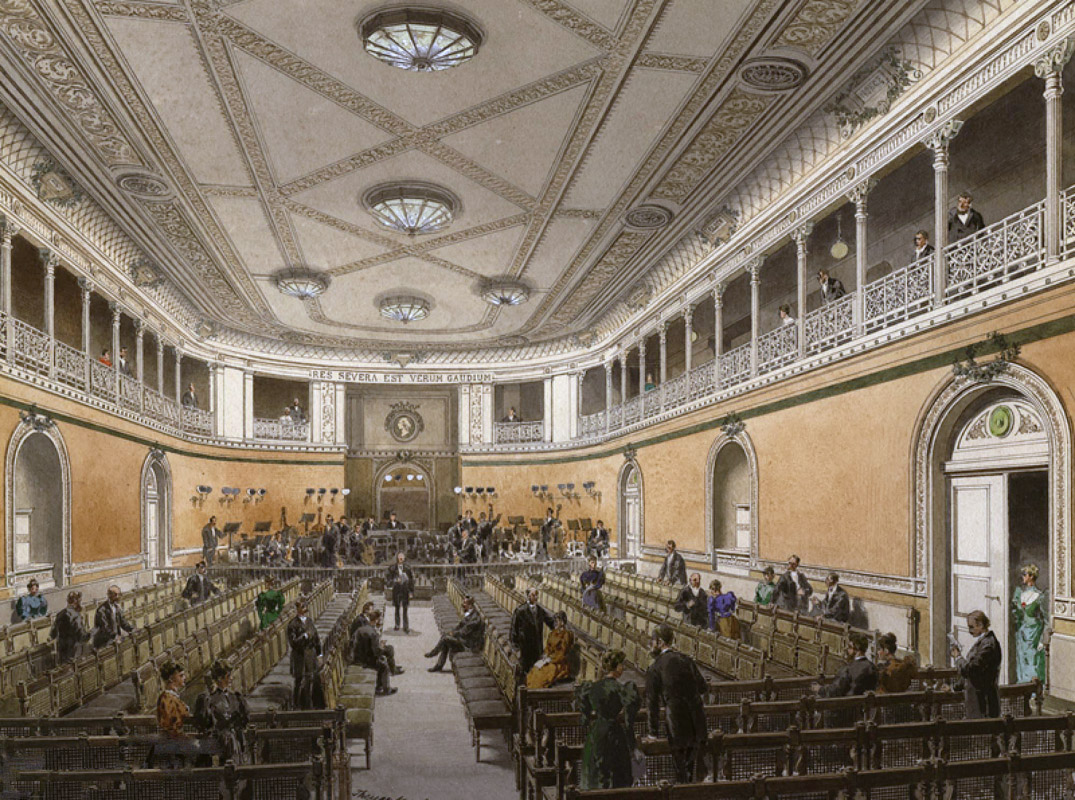

The first Leipzig Gewandhaus (1781) had room for 8.8 violins (sometimes standing). (Say 8.8.6.4.4)

500 seats.

In 1885 concerts were moved to a newly built hall, with room for up to 16.16 violins.

Did they use double wind I wonder?

SCHUBERT heard none of his symphonies played by a professional orchestra. His father’s schoolroom with a small band of amateurs was the norm for him.

If he had been lucky, 8.8. of the Opera would have been his ideal. He wasn’t lucky.

MENDELSSOHN and SCHUMANN (who lived in Leipzig) were of course used to 8.8.

BUT they were also used to a double orchestra at the Lower Rhine Festival (at Dusseldorf) in the summer.

I regularly used both, in the large version reducing suitable passages to single wind and 8.8 strings.

We can use both larger or smaller groupings and still remain historically truthful.

S for SEATING

Just as in Haydn or Beethoven the Violins were divided.

Horns and Trumpets likewise, Horns left and trumpets right. Basses central across the back.

S for SOUND

As I mentioned earlier, vibrato was known, but only as a decoration for soloists, not orchestras.

Maybe you’ve heard the atmospheric opening of Mendelssohn’s Reformation Symphony in my recording. When I played it with the Leipzig Gewandhaus Orchestra they were quite stunned by the effect. They had never heard it like that before.

And how about the beautiful Bachian slow movement of Schumann’s Second, again with Pure Tone?

S for SPEED

Schubert was still inhabiting Vienna, and the Viennese traditions of Haydn and Beethoven. For him the metronome was available, though he used it rather rarely.

Allegro was relatively steady unless increased by Molto, Con Brio etc.

Andante still moved along, but began to slow up little by now..

Adagio was gentle, rather than very slow.

Mendelssohn and Schumann were similarly used to Classical speeds, and some metronome marks help prove the point. Mendelssohn was at first surprisingly scornful of metronome, but he used it in some of his later works.

Schumann used it regularly, but some of his markings are difficult to understand, and for instance differ widely between the first and second versions of the Fourth symphony. No wonder he seems to have been pretty ineffectual conductor! In fact he suggested that a conductor should do very little beyond showing a change of tempo when the score asked for it.

S for STYLE

For our three composers many stylistic elements were naturally inherited from the Classical. But these elements do not seem to be so dominant as in the 18th century. Many markings are used for expression rather than grammar.

Spohr’s on-string at-point staccato was still common until Joachim’s time (late C19). But when Joachim asked Mendelssohn about springing staccato (our Spiccato) he said:

“Always use it my boy, where it is suitable and where it sounds well”.

Of course Paganini had used spiccato widely. Spohr called it showy and unsuitable for the Classical rep. David was so shocked by Paganini’s fantastic techniques that he thought of giving up the violin!

But spiccato off the string gradually became equally as expected as on-the -string.

For Schubert some grace notes may be still on the beat. But before the beat was becoming more frequent, for instance in the 2nd movement of the big C major.

For Mendelssohn and Schumann all grace notes were before the beat, as David showed.

sf, fp, szf etc seem quite interchangeable. Certainly in Schubert.

Schubert was much obsessed with accents, (for instance in the big C major.)

Mendelssohn and Schumann also used them,-for expression.

Mendelssohn wrote <> (ope of Symph 5). = Messa di Voce?

Written staccato began to differentiate between dots and strokes, though there was little agreement between composers as to which was which!

Mendelssohn did not distinguish between the two.

Schubert shows dots and strokes clearly in the big Symphony. Less clear is the difference between accent and diminuendo.

Some composers used a dot for on-string staccato, and a stroke (or Kyle) for off. Is that what Schubert means in the big Symphony? Brahms certainly used that convention later.

Trills beginning to be without an upper start.

For all our composers there was no expectation of added decoration, which had played an important role in the Classical period.